The flooring of the Palatine Chapel is made of

opus sectile

, composed of tiny marble tiles of different colours and shades; the large

porphyry tondos

(omphalos) come from circular sections of ancient columns.

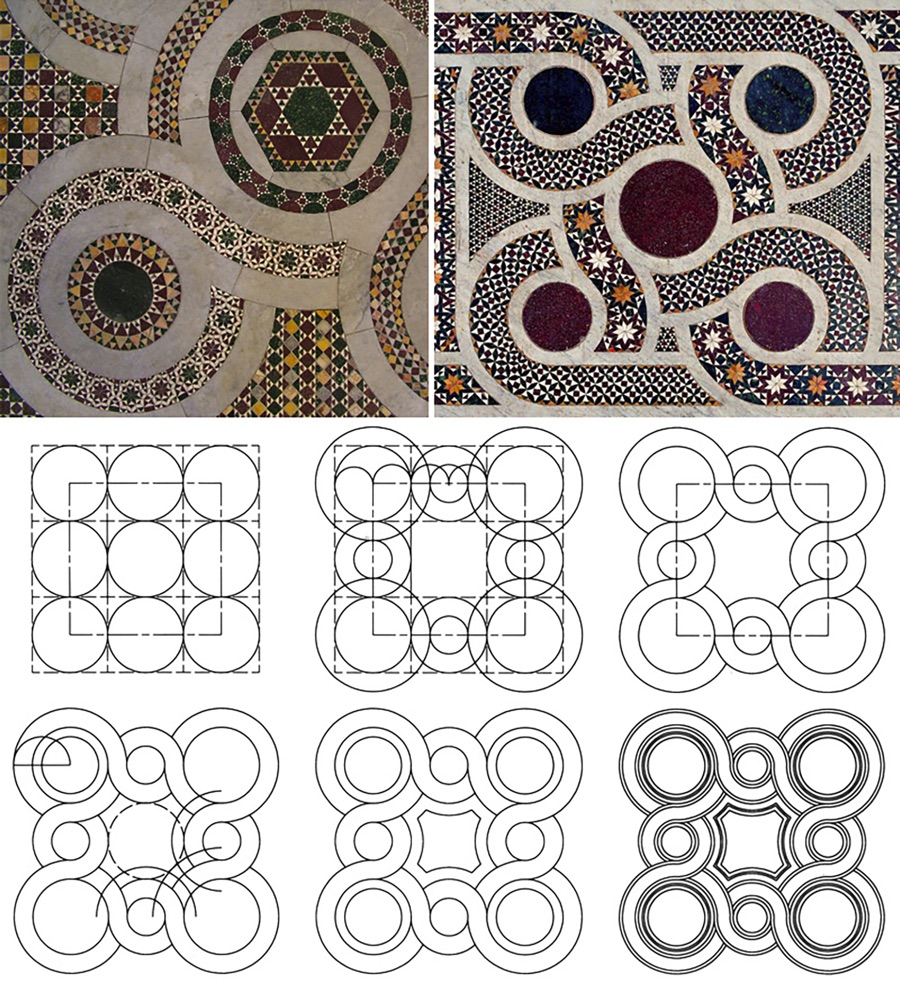

On the floor, an emblem of syncretism from the Norman period, complex lattice patterns coexist, intertwining to form starry polygons, typical elements of 12th-century North African and Egyptian architecture, and opus sectile, from the Byzantine mosaic tradition.

On the floor, an emblem of syncretism from the Norman period, complex lattice patterns coexist, intertwining to form starry polygons, typical elements of 12th-century North African and Egyptian architecture, and opus sectile, from the Byzantine mosaic tradition. Although the technique is oriental, the forms and stylistic elements are Islamic in style, and it is thought that both

Campanian Byzantineworkers

Although the technique is oriental, the forms and stylistic elements are Islamic in style, and it is thought that both

Campanian Byzantineworkers

, who had already worked on the Salerno Cathedral, and Islamic or Mediterranean craftsmen worked together. The floor is characterised by it’s division into squares with geometric motifs in which weaves, ribbons, triangular and circular elements, star-shaped polygons and

quincunx

or quincunxes recur.

The latter, as the word suggests, is an arrangement of five units and is configured with a central sphere and four lateral ones at the vertices. The motif, of Byzantine origin, was used mainly in

cosmatesquemosaics

The latter, as the word suggests, is an arrangement of five units and is configured with a central sphere and four lateral ones at the vertices. The motif, of Byzantine origin, was used mainly in

cosmatesquemosaics

.

The flooring is also part of Roger II’s ideological and political programme, which is expressed in the decoration of the Chapel, so much so that one of the most commonly used marbles is porphyry

The flooring is also part of Roger II’s ideological and political programme, which is expressed in the decoration of the Chapel, so much so that one of the most commonly used marbles is porphyry which, like purple, was a prerogative of the Eastern emperors due to its bright colour, being an ideal symbol of power and royalty. Other tiles, such as those in white, are made of locally sourced limestone marble. The same opus sectile floor decoration is present in the lower order of the walls of the side

aisles

which, like purple, was a prerogative of the Eastern emperors due to its bright colour, being an ideal symbol of power and royalty. Other tiles, such as those in white, are made of locally sourced limestone marble. The same opus sectile floor decoration is present in the lower order of the walls of the side

aisles

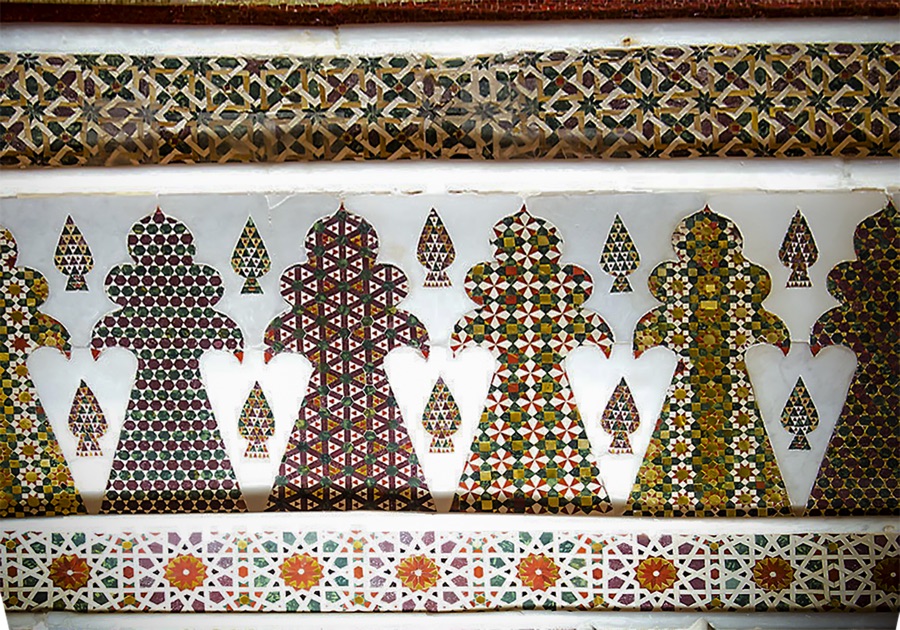

,

where the dialogue between western and eastern culture continues. A ribbon with a stylised palmette decoration of Islamic origin, also present in the

Monreale Cathedral

where the dialogue between western and eastern culture continues. A ribbon with a stylised palmette decoration of Islamic origin, also present in the

Monreale Cathedral

, joins and forms a caesura between the opus sectile and the Byzantine mosaics of the upper order of the naves.