Over five centuries, numerous renovations and modifications transformed the medieval building, which had typical Byzantine features and a very compact

Greek cross

layout. Today, the Church of Santa Maria dell’Ammiraglio denotes a mixture of different styles: the brightness and splendour of the Greek mosaics, with the figure of

Christ Pantocrator

At first, the layout was lengthened and the original façade with the

narthex

At first, the layout was lengthened and the original façade with the

narthex

was demolished. The atrium was covered and transformed, with the addition of the choir, supported by eight columns. In the following centuries, the fresco decoration was also completed.

Buildings such as Santa Maria dell’Ammiraglio, which the Arab traveller

Ibn Gubayr

Buildings such as Santa Maria dell’Ammiraglio, which the Arab traveller

Ibn Gubayr

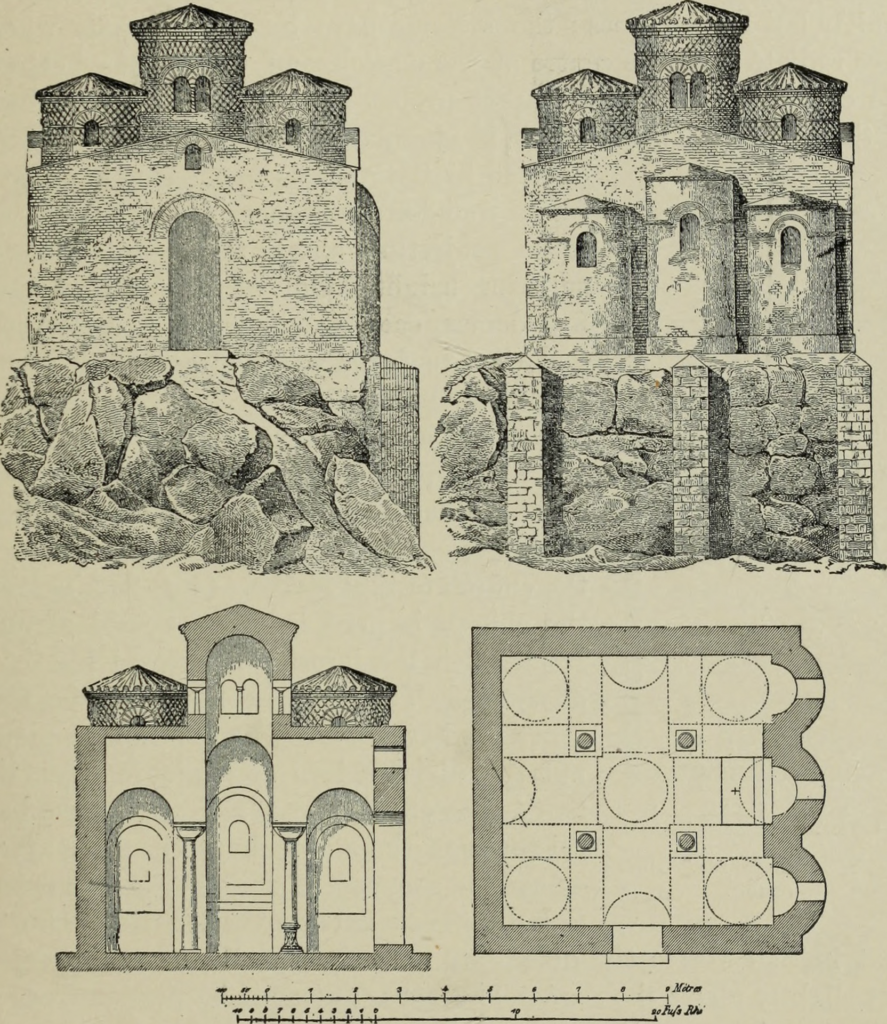

defined as “one of the most beautiful monuments in the world” with its original Byzantine style and centric plan, are examples of Greek architecture in Sicily, found in numerous buildings in Constantinople, such as San Giovanni in Studio, and comparable to the Cattolica di Stilo and other buildings in Albania and Serbia.

In particular, the Church of the Sopocani Monastery in Serbia, built around the 13th century, has the same solid and compact layout, a large porticoed entrance narthex and the bell tower in front, in axis with the building. The Martorana, however, differs from the Constantinopolitan buildings, where the exterior has a rather complex alternation of shapes and volumes.

In particular, the Church of the Sopocani Monastery in Serbia, built around the 13th century, has the same solid and compact layout, a large porticoed entrance narthex and the bell tower in front, in axis with the building. The Martorana, however, differs from the Constantinopolitan buildings, where the exterior has a rather complex alternation of shapes and volumes. The volumetry of the Church of Santa Maria dell’Ammiraglio is characterised by a compact, simple, square and robust form, typical of other Norman constructions which are rich in symbolic decorations, both in public and, as in this case, private buildings, alluding to the exaltation of temporal power.

The volumetry of the Church of Santa Maria dell’Ammiraglio is characterised by a compact, simple, square and robust form, typical of other Norman constructions which are rich in symbolic decorations, both in public and, as in this case, private buildings, alluding to the exaltation of temporal power. The artistic language, which is translated into certain architectural solutions, can be shared with that of the

Palatine Chapel

The artistic language, which is translated into certain architectural solutions, can be shared with that of the

Palatine Chapel

and

San Cataldo

, where, in line with the stylistic and programmatic choices adopted by

Roger II

, we note the same articulation of the roofs and similar decorative motifs in the marble flooring.